Looming Healthcare Apocalypse, Vol. 1: Why Women and Infants Are Dying in Rural America

How obstetric unit closures are putting rural families at risk.

If you, specifically, wanted to have a baby safely in America today, in our new year of 2025, could you?

The answer, as always is: it depends.

What it depends on is who you are and where you live. At a time when birth is increasingly being enforced, specifically on certain communities of people, the opportunity to do so safely is increasingly being taken away.

It is no secret that the US healthcare system has some abysmal indicators. Our country’s high maternal and infant mortality rates are so very unbecoming for a country of our development status, GDP and hefty healthcare expenditure. But that language is designed to distance and obscure. Let's be clear: This is not a crisis of maternal mortality for everyone. It is not a crisis of infant mortality equally distributed. The crisis does not affect some bodies, which are being privileged with life, and it does affect others, which are being sentenced to death.

This is happening on multiple fronts at once but for today let’s talk about one aspect of the crisis: the erosion of maternal care services in rural spaces. It echoes the ongoing consolidation of healthcare services and the increasing reach of private equity’s tentacles into the healthcare space. As if bodies were for shareholder profit.

Rural healthcare has always differed from urban healthcare. Difficulties in accessing care are endemic in both; even as a doctor in a wealthy city in a neighborhood overstuffed with hospitals and providers, I have a hard time getting care. But some things you can drive a distance for; some things you can't. Not everything can wait. Babies, for example, are notoriously poor schedulers.

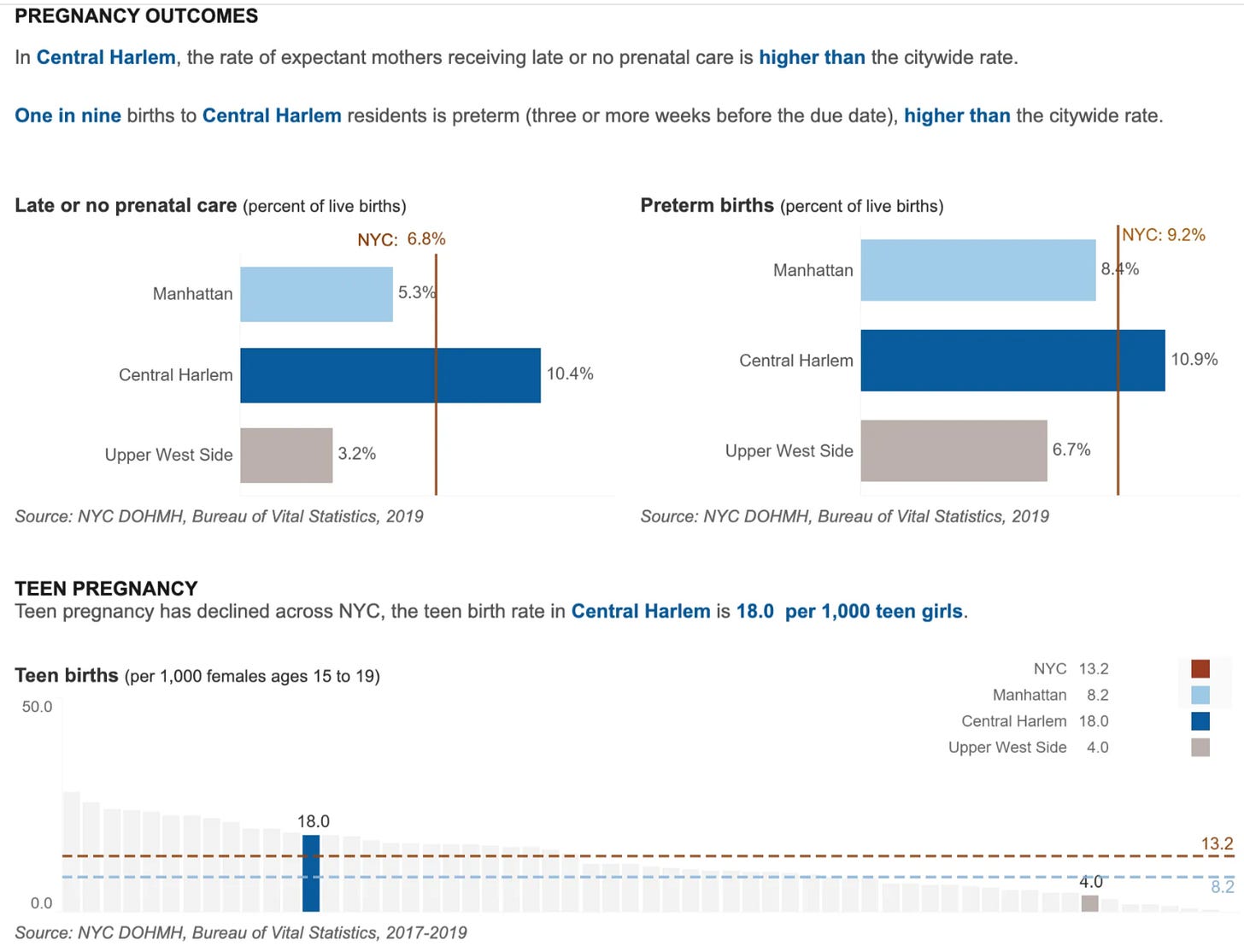

For decades, rural maternity and child health outcomes have lagged behind urban ones. This is about both quantity and quality. In urban centers, the problem often is one of variable quality. Care quality, as well access to care, can vary greatly by neighborhood, with massive differences in outcomes for people living only a few blocks apart.

For example, let’s look at two nearly adjacent neighborhoods in Manhattan, Central Harlem and the Upper West Side. The 2019 vital statistics data reveal huge differences in prenatal care, preterm births, and teen pregnancy. In Central Harlem, the rates of inadequate prenatal care are double that of Manhattan overall and triple that of its neighboring Upper West Side.1 The differences in pregnancy-associated maternal mortality go in this same direction; from 2016-2020 there were 5 deaths per 7191 births in Central Harlem and 2 deaths per 11483 births in the Upper West Side. 2 3

For many rural communities, there are problems of both quantity and quality. There are fewer places to get care. And patients in these communities often have worse outcomes. Increasingly, mothers simply do not have places to safely deliver their babies. Maternity units are closing in both urban and rural neighborhoods, but the impact is far greater for rural communities.

Closures have been increasing in recent years. There’s an excellent March of Dimes report from 2024 called “Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US” addressing this frightening reality. The report states that in the past two years, 1 in every 25 obstetric units closed their doors, leaving 1,104 US counties (and the more than 2.3 million women who live in them), without even one birthing facility or obstetric clinician.4 That’s in the past two years alone!

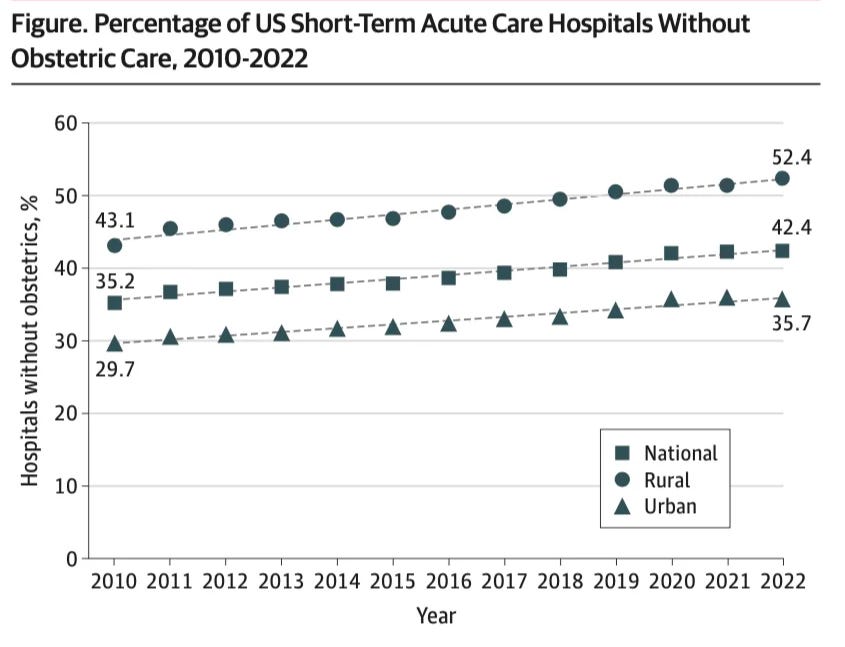

But this isn’t a new trend - it’s been ongoing for more than a decade, as highlighted in a recent JAMA paper by Kozhimannil and colleagues. In 2010, 43% of rural hospitals nationally lacked obstetric care; this rate increased annually until reaching more than 52% in 2022.5 Again: more than half of the hospitals serving rural communities cannot provide care for mothers and babies. Don’t call these communities deserts (though the March of Dimes report does), writes Kozhimannil in a BMJ paper in 2023.6 She points out that using the word ‘desert’ brings to mind a feature nature created that is largely empty, excepting some sand dunes and the occasional lizard. Instead, these are rural communities that lack maternity care due to structural violence, and which are often settled by BIPOC communities, including many indigenous people.7

What happens when so many obstetric units close? It doesn’t immediately seem that dire: ok, so people have to drive longer to receive care. But it’s not so simple. Public transportation infrastructure in rural areas is lacking. Driving long distances for pregnant women may be neither safe nor doable, especially if they are parents or caregivers. Someone needs to care for small children, or elderly or disabled relatives, while birthing people are traveling to care or are hospitalized. Each mile between home and hospital makes this harder.

In my work as a neonatologist, I often think about transferring patients to other centers. When you do transfer, there are only two options - you do it either too soon or too late. There is no perfect time. That will also be the case for parents in rural communities who have to travel ever farther. They can risk going too soon, being turned away, having to make another journey, leaving their kids behind, taking more time from work. Or they can wait to get care, and waiting can mean the difference between making it to the hospital in time for a safe delivery or not. In my line of work, for most term infant deliveries most of the time, everything is fine. But a proportion of term infants are not, and preterm infants always require subspecialty care. For these babies, the difference in life and death can hinge on seconds. Seconds, to put in a breathing tube. Seconds, to provide appropriate ventilation and properly clear the airway. Seconds, between having a healthy baby and having one that is neurologically devastated. The same is true for maternal care; much of the time things are fine. Except when they aren’t, and seconds make the difference between surviving a hemorrhage and exsanguinating from one.

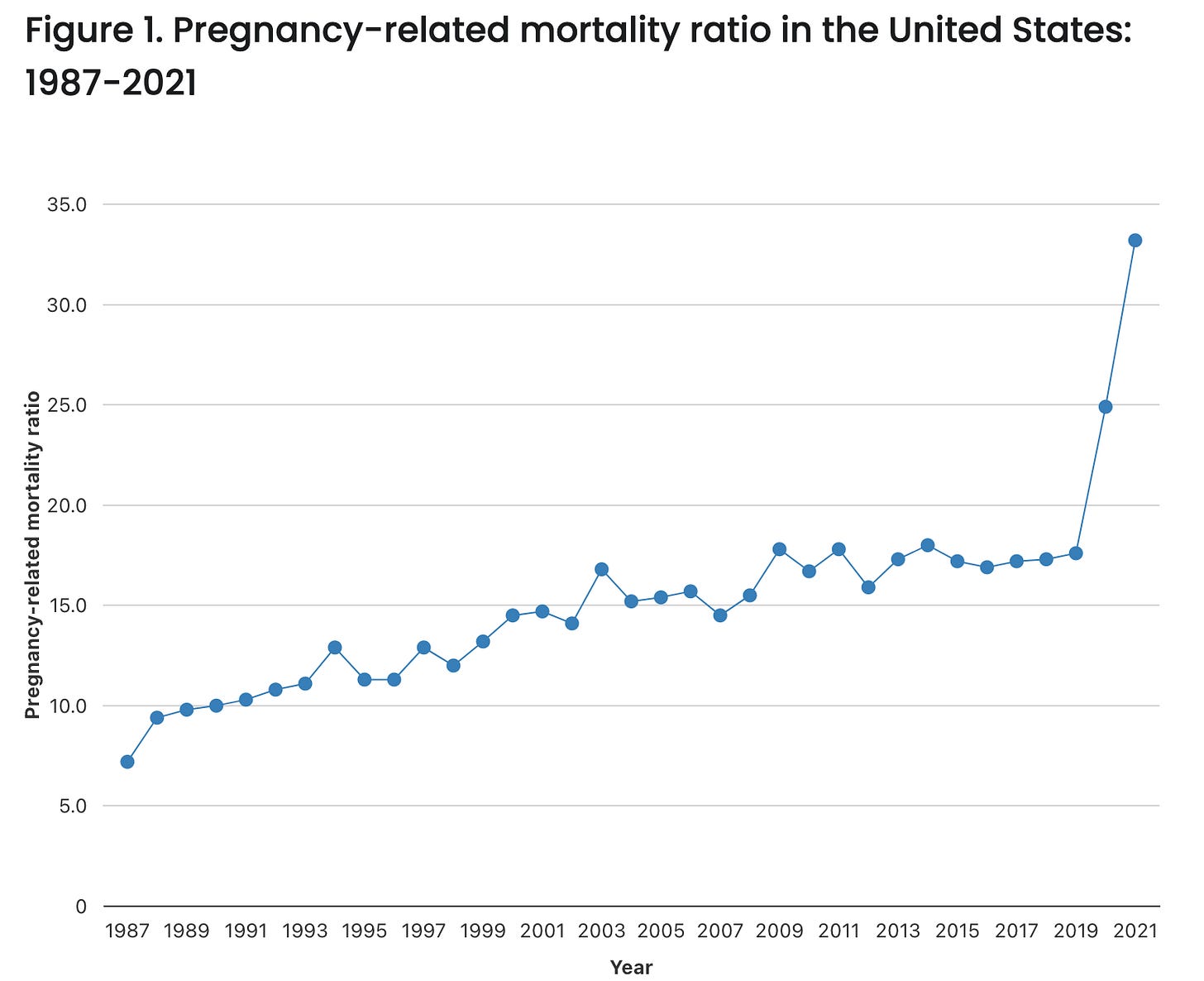

You can see this difference between life and death captured well in the US maternal mortality statistics. As obstetric care units closed, the pregnancy-related mortality ratio climbed:8

Pregnancy-related mortality was higher for those in rural communities, and is increasing. In 2017-2019 the pregnancy-related mortality ratio was 26 in rural areas; in 2021 it climbed to 41.

What I find so hard is that all of this is happening quietly, without enough fanfare. Where is the outcry? Where are the alternatives? In essence, these are lives that we are comfortable condemning.

What is there to do? I was taught never to come up with a problem without proposing a solution. But solutions feel in short supply. The problems are so entrenched, so systemic, so structural and long-standing. Defeat feels easier to reach for. Apathy beckons.

But let’s roll up our sleeves. First: daylight is a terrific disinfectant. Well, metaphorically speaking (otherwise I think you need water and soap). But telling the truth about this is important. Tracking this is important. Holding elected officials accountable is important.

But what about those of us in urban centers? Or those who are not trying to give birth? It's easy right now, in the wake of the UnitedHealthcare CEO shooting, to speak in broad terms about American healthcare. Sure, I agree—we do have lousy outcomes for how much we invest in healthcare, but these outcomes are specifically lousy for the poorest people, for people in rural communities, for people whose primary language is not English, for trans people, for people of color.

Being specific about what we say is a kind of respect; not being specific is a kind of elitism. It gives the lie to the privilege of those who are not reflected by the grim statistics. Specificity is free, if uncomfortably illuminating. Maternal and infant mortality in the US is so poor, in part, because rural obstetric units are closing at an alarming rate. Women are being forced to give birth by the lack of access to appropriate and safe contraceptive and prenatal care, and once they are forced to, they cannot do so safely. We need to speak it plain: we are setting women and babies up to die, we are setting up families to suffer, because it is unprofitable and logistically difficult to do otherwise.

I asked you earlier whether you, specifically, can give birth safely in 2025. For most people reading this, I think the answer is probably yes. But a lot of people can't, and we need to be specific and we need to be loud in discussing this and pushing for change.

Have you or your loved ones ever struggled to access the care you needed? Tell us in the comments.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Profiles - Manhattan 110: Central Harlem. Viewed 1/10/2025 at https://nyc.gov/health/profiles

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Profiles - Manhattan 107: Upper West Side. Viewed 1/10/2025 at https://nyc.gov/health/profiles

Maternal Mortality Review Committee, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Pregnancy-Associated Mortality in New York City, 2016-2020. September 2024.

Stoneburner A, Lucas R, Fontenot J, Brigance C, Jones E, DeMaria AL. Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US. (Report No 4). March of Dimes. 2024. https://www.marchofdimes.org/ maternity-care-deserts-report

Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Carroll C, et al. Obstetric Care Access at Rural and Urban Hospitals in the United States. JAMA. Published online December 04, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.23010.

Kozhimannil KB. Declining access to US maternity care is a systemic injustice. BMJ. 2023 Sep 7;382:2038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2038. PMID: 37678911.

Kozhimannil KB. Declining access to US maternity care is a systemic injustice. BMJ. 2023 Sep 7;382:2038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2038. PMID: 37678911.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Accessed 1/10/2024. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance/index.html#cdc_survey_profile_how_the_information_is_used-pregnancy-related-deaths-by-urban-rural-classifications

Disclaimer: The content provided in Couch Nap is for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It does not establish a doctor-patient relationship. Always consult with your healthcare professional regarding any medical concerns or decisions. The views and opinions expressed here are our own and do not represent the positions, policies, or opinions of our employers or any affiliated organizations. While we strive for accuracy, the information presented here may not apply to your unique situation.