The news has been relentless: a brutal flu season, a measles outbreak claiming young lives, and the first measles death in the US since 2003. As pediatric critical care doctors, we're not just reading headlines; we're living them. We're witnessing the consequences of declining childhood vaccination rates and the rise of misinformation, a dangerous combination that's eroding public health and putting vulnerable children at risk.

It's not just about individual choice anymore. We've seemingly lost sight of the crucial role of community responsibility in public health. The idea that we have a mutual obligation to protect ourselves and those around us through evidence-based vaccination recommendations seems to have faded.

We’ve been talking a lot to each other these days about what it’s like to work with unvaccinated populations. But we wanted to tell you about it, too.

The Neonatal ICU:

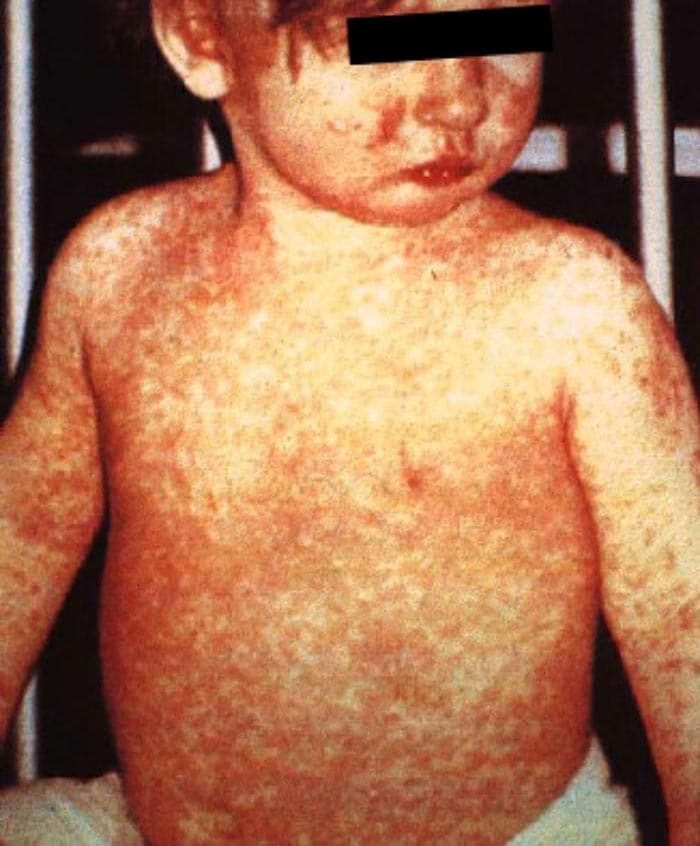

Many doctors in the U.S. are fortunate to have never seen measles. I'm not one of them. During my training, I saw a handful of cases, mostly kids who needed respiratory support for pneumonia but ultimately recovered. In med school, every test has questions on the the measles classics: the 3Cs (Cough, Coryza [medical-speak for runny nose], Conjunctivitis), the telltale morbiliform rash (red splotches that cascade down the body like someone dumped a paint bucket from the top of the head) and the characteristic throat spots. What they don't prepare you for is congenital measles in a 25-week premature baby.

From 2018-2019, New York (NYC and nearby Rockland County) had a measles outbreak, with at least 649 confirmed cases of infection, mostly in people <18, who predominantly were the unvaccinated and undervaccinated members of Orthodox Jewish communities. One of those women had a 25 week old baby that I cared for.

The baby

Most people can’t picture a 25 week old baby. This baby was on the larger side at 840 grams (slightly bigger than a Venti at Starbucks; picture a 1L soda bottle and subtract 3 Reese’s peanut butter cups). Mom developed symptoms several days before delivery; she underwent a c-section and had to stay away from her baby until her symptoms improved.

All 25 week infants are extremely vulnerable with super immature lungs; all of them have protracted NICU stays with many challenges. Because of the measles, this baby had to stay in a negative pressure room. Visitations were limited in the whole NICU, and mom was not able to see this baby for approximately two weeks. The baby had to receive immuneglobulin as post-exposure prophylaxis, and got vitamin A as well. The baby was still shedding virus more than a month later (urine PCR was positive at 36 days); it took until she was 60 days old to be cleared from the negative pressure room, following two negative PCRs. Her brain imaging remained reassuring throughout her course, including head ultrasound and MRI.

This baby did as well as could be for a 25 week infant and an infant with congenital measles at that. That said, the literature shows she’s unfortunately not out of the woods when it comes to SSPE, a deadly complication.

Congenital measles

We know pretty little about what congenital measles looks like, especially in very preterm infants. In order to get congenital measles, the birthing parent needs to be infected during pregnancy, close to delivery. In the pre-vaccination days, most people got measles as children, and now in the vaccine era, most people are vaccinated by 4-6 years old. Thus, in both cases, people are largely immune by the time they are pregnant. Data about congenital measles comes from case series, and information on such extremely preterm infants with measles is pretty scant.

We expect, based on these case series, for infants with congenital measles to develop the characteristic rash. In fact, some definitions try to distinguish congenital and post-natally acquired infections based on rash timing. But preterm infants don’t necessarily get the classic rash; this baby didn’t, and other babies in the literature also haven’t. Symptoms, like the rash, and severity of presentation are variable, as are treatment plans. We gather information piecemeal and proceed as best we can.

SSPE, a deadly result

What the literature does show is a consistently higher risk for infants with congenital measles to progress to SSPE (or subacute sclerosing pan-encephalitis), a fatal complication that shows up years after the initial symptoms have faded way. How many years? I’ve seen a range of 2-34 years quoted in the literature, but for infants with congenital infants, a period of totally normal development can be followed by a much shorter window than typical (a few months-years) before SSPE begins.

SSPE is brutal and hideous. There is progressive neurological decline, first with a loss of cognitive milestones and then seizures, spasticity, severe progressive muscular decline and then death. A horrible condition with so much suffering for everyone involved.

You may think I’m relieved this baby did so well. And I am, but I’m very nervous about the risk of SSPE. The brain, like the lungs, is very immature and undergoing a period of rapid development at 25 weeks. Not enough data exists, but I can’t imagine that being exposed to measles at such a critical period of development isn’t somehow tied to the higher risk (some estimates say up to 16x) and shorter interval before development of SSPE.

I’ve told you what it’s like for the baby. But the ripples go so much further:

The mother

Separated from her critically ill 25 week baby during those crucial first days, when mortality risk is highest.

Living with the knowledge that her unvaccinated status exposed her daughter to a preventable disease with potential for a brutal, untreatable fatal complication years down the line.

The care team

Wasting precious seconds in a code situation donning and doffing PPE. Seconds are what matters if a breathing tube dislodges or a ventilator stops working.

Stretching already thin staffing to accommodate isolation protocols.

Balancing personal risks—pregnant staff, those with immunocompromised family members—against professional duties. I had conversations with many staff members who were hesitant to care for this infant.

Spending hours, so many hours, in meetings with the infectious disease, infection control, Department of Health and other stakeholders. These are important meetings, but if you have to spend two hours a day on them, that is two hours less to update and comfort parents of other babies.

Outfits like this can take ages to put on and take off between patients. Also you get extremely, horribly, sweaty. Image here.

Parents of other infants

Worrying about the risk of infection in their own babies; having to adjust to more restrictive visitation policies

Witnessing staff in full PPE and wondering: "If my baby codes, will they reach her in time?"

The Department of Health

Those are just the measured costs to one department. Imagine all the other costs involved.

All this, for something preventable. Something that absolutely did not have to happen.

I remember this baby. She was very sweet. None of this was her fault. But that’s how it always is, isn’t it? It’s not as simple as reaping what you sow; someone [selfishly] sows, and someone vulnerable reaps. Ripples are felt everywhere.

The Pediatric Emergency Department

While Dr. Vicky is navigating the delicate scenarios of vertical transmission of infectious diseases in the tiniest and most vulnerable, I am more familiar with the direct consequences during the winter viral season. This winter, our emergency department (ED) has become a living, breathing testament to the consequences of vaccine hesitancy. While the annual flu shot doesn’t full prevent risk for contracting the flu, it reduces the seriousness of symptoms and need for hospitalization.

Flu vaccination rates are down across the board, except in Iowa (huh?).

Don’t get me wrong, I’ll treat any sick child who comes through those doors, but I absolutely need to ask vaccination status because it will impact your child’s care. I spend a lot of time thinking about how preventative interventions seem so abstract until it is your kid struggling to breathe but it is exhausting to have the same conversation that yes, vaccination could have reduced the likelihood of this current infection.

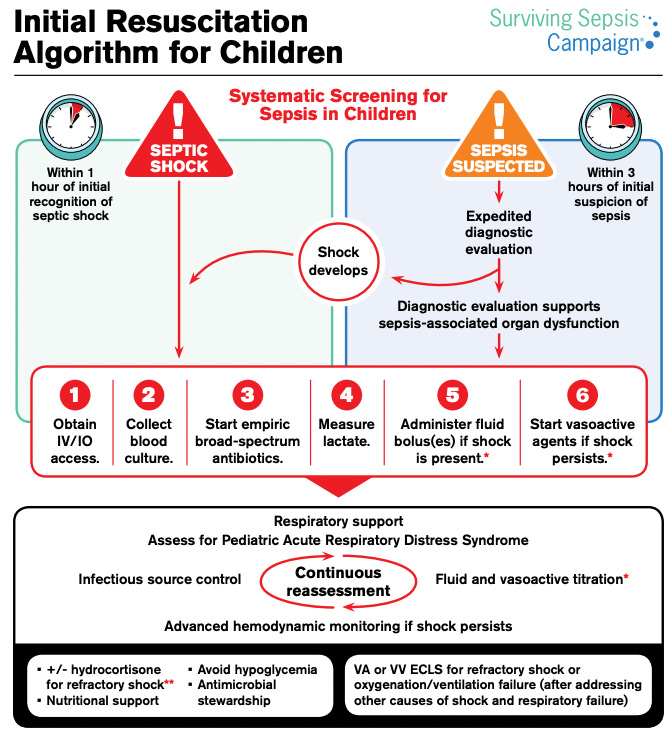

I keep circling back to a recent case because not only was the child incredibly ill but the ensuing interaction to provide care was, shall we say, challenging. Picture an 8-year-old girl, pale and sweaty, heart racing, barely responsive. Her breathing was shallow and rapid, 60 breaths per minute and her oxygen saturation a terrifying 86%. Normal for her age should be 18-24 breaths per minute and oxygen in the high 90s. We’re in a suburban ED so limited pediatric resources. When a kid arrives this critical, we move fast. IVs, antibiotics, fluids, breathing support, time matters. And forget about our usual trauma-reducing techniques, no time for gentle explanations.

This little girl, it turned out, was unvaccinated: no childhood vaccines, no annual flu shot. Every treatment decision became a battleground. Initially, her parents would only allow half-dose fever medication, terrified of “over-medication.” Questions about the type of IV fluids, the necessity of antibiotics, every single step was met with suspicion and resistance. In another scenario, it would be valuable to understand where this fear was from and I always remind myself that parents’ reactions are often grounded in fear, guilt and concern. But it’s exhausting. And worse, it’s dangerous, because in scenarios where we are concerned about sepsis (widespread infection and the immune response to it), timing of interventions matter and more importantly impact whether this little girl will survive.

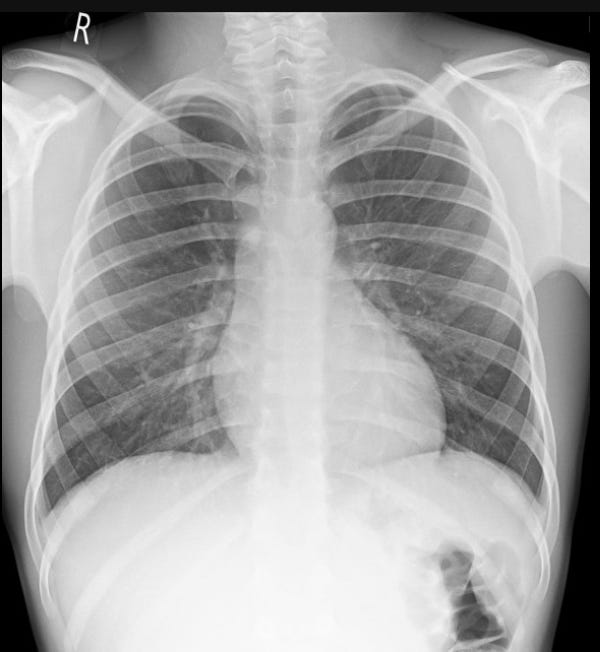

Ultimately, she had influenza A complicated by a massive pneumonia (an infection in the lungs) with fluid filling almost the entire half of her chest.

We had to give multiple antibiotics to stave off bacterial coinfections that other childhood vaccines could have prevented. We had to use positive pressure ventilation - imagine a CPAP machine but intensely uncomfortable, forcing air both in and out. It was a brutal necessity and we had to give medications to keep her comfortable while using the respiratory support. She needed the pediatric intensive care unit (a PICU), a level of care we couldn’t provide.

The team was stretched thin, with many other patients to see, but after a blur of phone calls, we secured critical care transport and a PICU bed – a precious commodity these days. We were lucky - sometimes it has required long transports (even out of state!) a situation that is baffling to families who can’t imagine that hospitals couldn’t just make space to take their child.

And while this seems better suited to TV drama (I still refuse to watch “the Pitt”, it’s too close), her mother stepped out of the room and asked if I sincerely believed that a flu shot would have made this better. Without hesitation I replied: “While I can’t possibly predict what would have happened, I know that the flu shot helps prevent hospitalization and spread of infection and I recommend it for my loved ones of all ages every year”. Whether this truly landed in a night of many challenges, I’m not sure — I hope so. Or maybe, after she recovers, this memory will fade too, lost in the noise of the next viral conspiracy, the next anti-vaccine article.

What can you do?

Ensure you are immune. If you aren’t certain or are worried your immunity may have waned, you can get your titers done (Dr V here - my mumps titers were low, so I needed a repeat too).

How cute is this? From the UK. Plan ahead if you’re considering pregnancy. Live vaccines like the MMR are not given during pregnancy, so the ideal time is 4+ weeks before conception. There are safe versions of the annual flu shot for individuals who are pregnant.

Pregnancy is an especially vulnerable time for those infected with measles, with higher likelihood of mortality and complications (such as hospitalization, pneumonia, miscarriage, preterm labor and infant mortality).

Your ob may not bring this up proactively; surveys report that ob-gyn providers feel providing information about childhood vaccines falls outside their scope of work. This presents a missed opportunity since for some people, their ob-gyn is the doctor they see and trust the most; many patients do not have or rarely see their PMD.

If you are seeing your ob-gyn, ask them about vaccines you can get and how your vaccine status may affect your pregnancy. Additionally, there are recommendations about treatments that might be required (Tamiflu for influenza in pregnancy)

Get recommended annual vaccinations and boosters, if you are eligible. This includes annual vaccines like flu, and vaccines that people are eligible for based on age or pregnancy status (for example, the RSV vaccine, the shingles vaccine).

Support public health infrastructure. Those 559 people at the Department of Health that worked to contain the 2018-2019 outbreak are at risk now. The CDC fired disease detectives and vaccine messaging, disease surveillance, and healthcare infrastructure are all being dealt mortal blows by this administration. Call your representatives (it’s easy: 5 calls!).

Be mindful of disease hotspots. True for measles, true for flu, true for any other contagion. If you’re in a high traffic area for infections, protect yourself. Some of my patients have started screening potential pediatricians to eliminate those who accept unvaccinated families. Any time you are in a place where diseases hang out (emergency departments, urgent care, doctor’s waiting rooms) or easily spread (airports, subways, crowd events like sports), think about wearing a mask.

Convince the convince-able. We don’t waste time preaching to the unreachable. They’re too far gone. And we don’t have time. There is plenty of excellent science showing that the MMR vaccine no more causes autism than it causes children to turn into a turkey sandwich; we don’t feel a need to reinvent that wheel. We don’t need to repeat that as pediatricians, we are not receiving pharmaceutical kickbacks — pediatricians will never be the money-makers (most pediatric departments lose money overall, and most vaccines lose money for their pediatric practice). We have to save our energy for people who do have an open mind about the MMR vaccine or questions about the consequences of measles.

Don’t give nonsense airtime. Don’t reward the algorithms’ various attempts to seduce you with baloney. Don’t get sucked into reels, discussions, or posts full of misinformation. Don’t hate-share things; indignation and outrage amplifies creator growth just as much as love does. Follow and amplify those creators in social and traditional media who are evidence-based and who engage thoughtfully and admit nuance (we love Inside Medicine, Examined, the Vajenda, Your Local Epidemiologist, Unbiased Science, and Beyond the Noise).

And because we can’t let you go with just the dire, have a picture of a pile of puppies. Because dogs are still the best.

Photo by Jametlene Reskp on Unsplash

Disclaimer: The content provided in Couch Nap is for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It does not establish a doctor-patient relationship. Always consult with your healthcare professional regarding any medical concerns or decisions. The views and opinions expressed here are our own and do not represent the positions, policies, or opinions of our employers or any affiliated organizations. While we strive for accuracy, the information presented here may not apply to your unique situation.