It's In Their Bones: What fractures can (and can't) tell us about abusive injury.

Examining bony injuries in the wake of a recent NICU nurse arrest for child abuse.

Before we get into this week’s Couch Nap, I want to acknowledge the current healthcare (and overall) landscape. The news is moving fast and there are multiple destabilizing changes to the US healthcare system. At Couch Nap we are grateful for the work of Inside Medicine, Abortion Every Day, Law Dork, LIL Science, Your Local Epidemiologist, and News Not Noise for keeping us informed. I recommend you check them out. As I despair of the news from the safety of my couch, I am thinking of those in L.A. who are not as lucky; consider contributing or helping animals. Finally, for a bit of healing, here is a purring cheetah cub.

Content warning:

This post contains a discussion of child abuse. This is an important but a painful subject; please skip this if that is what is right for you.

“I fell in the snow!” Javeon1 insisted. “No one did nothing to me.” His legs were dangling off the stretcher, a tiny boy on a big bed, clutching a pack of animal crackers. His brother was busily coloring nearby. “We were playing outside and we fell.” His back was a patchwork of bruises. One was the precise shape of an adult’s belt buckle. A large adult with a big belt. It had snowed maybe an inch, several days back. This wasn’t from falling in the snow.

That night in the emergency department was 9 years ago, but I still think about Javeon and his brother. That belt buckle imprint on his skin won’t ever leave me.

Every doctor has the thing they hate: for some it’s feet (you have no idea what I’ve removed from some patients’ toes!), for others it’s the mouth (ditto!). I tend to find eyeball-related things pretty gnarly. Some doctors dislike dealing with cancer, or pregnancy, or death. As a neonatologist, I work primarily with babies in the NICU and nursery. I see plenty of tragedy. However, it is no small gift that this is the one area in pediatrics where you can largely evade child abuse.2

Medical abuse

That is, until recently. Like an episode of Law & Order SVU: UK: NHS edition, there was the horrific case of Lucy Letby, a nurse from Herefordshire. She was charged with 7 counts of murder and 15 counts of attempted murder (although this New Yorker article makes a compelling argument for reconsidering the investigative process and maybe the whole case).

A few weeks ago, a similar story unfolded closer to home, in Henrico County, Virginia. Nurse Erin Strotman was charged with malicious wounding and felony child abuse for a November 2024 incident. Allegedly there is a video of her breaking an infant’s bones. Multiple infants were found with fractures. Seven cases in the hospital are under review and the NICU has paused admissions.

This beggars the imagination. I thought I’d seen it all. But the NICU, though? What kind of monster? And how?

I can’t speak to what kind of monster would do what these nurses are accused of. In my experience, monsters come in all shapes and sizes. Some can be very sweet, and even pious, all the while doing their unspeakable dirt at home.

But I can speak to bones, and the secrets bones can reveal. Bones are a useful source of information during investigations of child abuse, and there is a new American Academy of Pediatrics report, hot off the presses from February 2025, about the evaluation of bony injury in child abuse. I can also speak to how preterm infants’ bones are different than those of term infants and older children. If we must be horrified by all this, let us also be informed by the science.

The scope of the problem

The numbers are ugly. Abuse is intolerably common. The American Academy of Pediatrics estimates that 1 in 7 children experienced abuse or neglect in the last year. One in 4 experience abuse or neglect in their lifetime. Far too many children die; in 2021 nearly two thousand children - 1,753 to be exact - died from abuse or neglect in the US.

I suspect these numbers may underestimate the problem. Not all abuse leaves a mark. Many injuries and other traumas heal without ever being evaluated by healthcare providers. Even when injuries are evaluated, they're easy to miss: up to 20% of fractures from abusive injury in children under 3 years old are initially misdiagnosed. When injuries prompt skeletal surveys (screening imaging protocols to check for fractures in young children), additional injuries are found in up to 10% of all patients and up to 25% of infants. When these surveys are repeated, up to 20% yield new information.

This is how tricky the work is. And that's before we even get into the actual mechanics of how bones break.

Why do bones break?

Bones can break for several reasons:

Accidental trauma. The bones were properly formed. They were injured in the course of unintentional trauma and we have a reasonable explanation. For example, a toddler crawling somewhere they shouldn’t be, an aging potato wife like me busting a hip on the ice, or someone sustaining an injury during sports (which would never happen to me because I would never sports).

Non-accidental trauma. The bones were properly formed. They underwent an injury in the course of abusive trauma. We will talk more about this case below.

Structural changes. The bones were once properly formed. However, they have undergone maladaptive structural change, predisposing them to injury. This can be due to a disease process such as chronic liver or kidney disease, a medical treatment, prolonged immobility, malnutrition, or a combination of all of the above.

Genetic disease. The bones were not properly formed due to a genetic condition, making them prone to breakage. This can happen with many kinds of genetic conditions, some of which are inherited and others that arise de novo. There is a tremendous variety of these skeletal dysplasias which range from milder conditions to lethal ones.

Some of these conditions are deadly in the neonatal period, since the bones are so abnormally formed that other organs can’t function properly; others deposit abnormal bone composition over time; still others have bones that may look and function reasonably well but are very brittle. I’m lumping these together, but this category has great heterogeneity, and even the variety within a single disease is vast, as each condition presents differently in every patient. The bottom line is, bone formation is not normal due to genetic reasons.Prematurity. The bones were not properly formed due to prematurity, making them prone to breakage. This is why the discussion of the alleged actions of Erin Strotman can be confusing: how does any baby already in the hospital, with 24/7 monitoring, sustain a fracture? Can anything besides abuse account for a fracture in a continuously observed baby who is supposed to be safe?

Well, there are the genetic conditions as above, which can predispose to fracture. They are each individually infrequent but there are indeed many of them. That’s one possibility. Additionally, many term infants have broken bones due to birth trauma. The clavicle is snapped most often during deliveries, and tends to heal well and with minimal fanfare and no intervention. Other bones need more effort and cause more pain but do heal. These fractures are evident at birth, however, not at a later juncture.

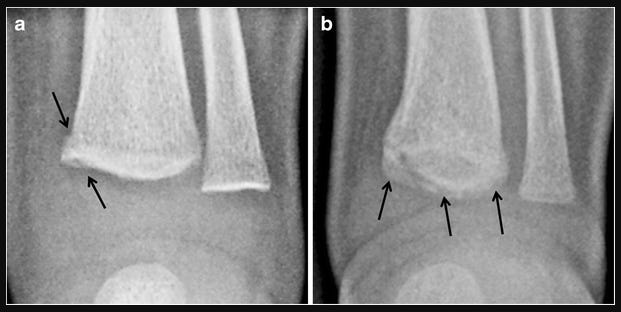

Preterm infants sustain fractures for a different reason. For them, broken bones are often the result of osteopenia or what we call metabolic bone disease of prematurity, rather than birth trauma. Their bones are abnormally mineralized and especially fragile.

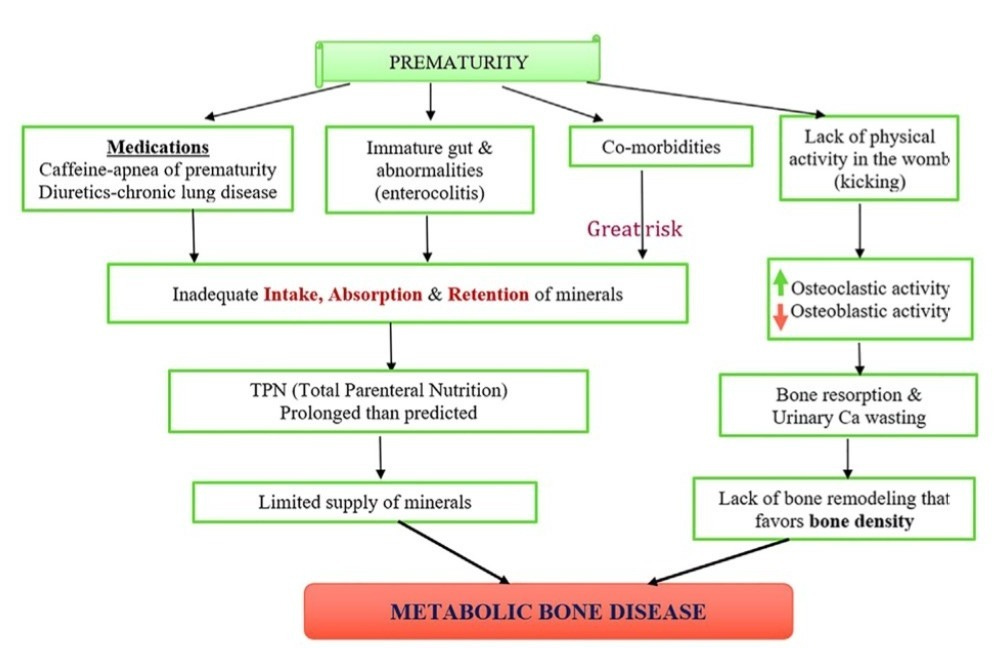

The simplest diagram of metabolic bone disease I could find. From Clinics in Perinatology Preemies, especially those at the younger extremes of prematurity, miss the bulk of the placental transfer of calcium and phosphorous, which occurs in the third trimester, and which provides the building blocks for a strong bone matrix. These infants are also often missing out on healthy developmental movement; the benefits of water aerobics while swimming and kicking inside amniotic fluid are far greater than the poor mobility of prolonged laying in an incubator box. Finally, preemies often have some degree of malnutrition and sicker babies are frequently exposed to medications (such as diuretics and steroids) that leach minerals from bones and weaken existing structures. These babies’ bones can look wispy and translucent on x-rays in severe cases.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t take much to cause a fracture. For very under-mineralized bones even routine handling such as diaper changes, vaccine administration or the squeeze from a blood pressure cuff can cause a fracture. That’s why cases such as the one Erin Strotman is accused in can take time to come to light.

A lack of specificity

In an ideal scenario we would easily distinguish these causes. Bones broken due to abuse would have obvious, characteristic, unmissable patterns that only occurred with abusive injuries. The Venn diagrams would never overlap. It would be like on TV: clarity, a smoking gun and swift justice. But it’s rarely that simple.

There are certain kinds of injury that are more likely to be caused by abuse than by anything else. It’s worth going into a bit of detail here, because you may notice something on a child and spare them injury and trauma.

Some of this is intuitive. Children who aren’t yet independently moving much are unlikely to have the same injuries as those who are climbing into your cabinets and leaping from your couch. You can’t cause yourself a high-energy bony injury if you aren’t very mobile. Thus, it makes sense that up to 25% of fractures in children < 1 year old are from abusive injury; these kids are not yet great at walking or getting up on high surfaces.

This is true for bruises as well. Bruises are the most common presentation of injury from abuse, though most fractures in abusive injury are not accompanied by bruises. I was trained to remember “you don’t cruise, you don’t bruise,” which still stands to reason, as well as the acronym TEN-4.

TEN-4, which has now been expanded to TEN-4-FACES-p, is a mnemonic reminding us to consider abuse when we see bruises in certain spots in kids younger than 4 years old. TEN stands for Torso, Ears, and Neck, and FACES stands for Frenulum, Angle of jaw, Cheeks, Eyelids, Subconjunctivae. A doozy of an acronym. Some spots are harder to bruise accidentally than others, even for squirmy tyrant toddlers. Under four years old, these spots merit additional consideration; under four months old, any bruise is a worrisome herald of child abuse. True, bruises can also be a sign of a bleeding or clotting disorder, but those, like skeletal dysplasias, are relatively uncommon compared to child abuse. Bruises shaped like weapons (hands, cords, belt buckles) should always prompt concerns for abuse.

Unfortunately there’s no similar helpful acronym for bony injuries.

However the American Academy of Pediatrics does classify some injuries as being more specific for child abuse than others, as you can see in this table:

In addition to the kind of injury itself, the context of an injury is critical to help distinguish accidental from inflicted trauma. It’s one thing when there is an explanation like a witnessed fall from the monkey bars. Injuries without a clear story get murkier, or cases where there was a delay in getting evaluated or with multiple injuries. The lack of a plausible mechanism, a multiplicity of injuries, a delay in obtaining care; all these taken together could be what happens in an accident. But they must ring an alarm for considering abusive injury.

It’s easy to say that from inside the healthcare establishment. How could you not seek care for your injured child? How could you allow injuries to accumulate? And yet, there are good reasons that many families hesitate to be evaluated.

People may be worried about the cost of evaluation, or concerned about their insurance or documentation status. They may be unaware of the seriousness of the injury or unsure who to seek evaluation from - the ED, a specialist, their doctor. There may be the same delays in accessing and communicating with healthcare providers that we all experience. Many families are also mistrustful of the medical system’s history of implicit bias and inequitable treatment. Parents may have guilt or shame, or may fear retribution from other family members for seeking care. Teasing out the circumstances of an injury and the milieu of a family is a delicate act that should be handled with finesse and respect.

Specialty care

Distinguishing abusive from accidental injury is challenging, high stakes work. The risks of misdiagnosing abuse and keeping children in an unsafe environment are great; conversely, the costs of suspecting families erroneously are not insignificant. There’s a whole subspeciality of pediatrics dedicated to this, Child Abuse Pediatrics, which requires three years of training after residency and an emotional fortitude I personally do not posses. These doctors are skilled at obtaining histories from children while minimizing additional trauma and confusion, evaluating injury patterns to determine cases of abuse, and liaising between medical, legal, law enforcement, and social work teams.

Unfortunately, they are in short supply; in 2023, there were less than 350 Child Abuse Pediatricians in the whole country.3 Compare that to the 1 in 7 US children who would benefit from their expertise each year. And there are very tangible benefits to their expertise. Having worked and trained with several such experts, I can speak firsthand to the kind of thoughtful, patient, measured person that goes into that field. The outcomes bear this out. Most children end up being seen in community hospital emergency departments (though, please, if you have anything more serious than a paper cut, go to a children’s hospital if at all feasible4) rather than pediatric EDs. These community emergency departments are more likely to miss abuse. Steps are being taken to mitigate this disparity by identifying local champions in the absence of Child Abuse Pediatricians, and by standardizing protocols for evaluation, but there remains a ways to go.

Certainty is too late

Pediatricians are mandated reporters. We are obligated to report our concerns for abuse long before there is confirmation; confirmation is too late. You want systems to be sensitive to the possibility of abuse and err on the side of ensuring the safety of children. Unfortunately, implicit bias and disparities persist, and lead to both over-reporting and under-diagnosing abuse in certain groups.

Nor, in my experience, have the systems responsible for ensuring children’s safety been agile or deft or equitable in their responses. Children are returned, often multiple times, to dangerous homes, or sometimes sent to foster in worse ones. There are good outcomes too, don’t get me wrong. But they can take multiple attempts and are not guaranteed. It’s not the system I would hope for.

I wish I could tell you that children are remarkably resilient and it usually turns out well. I can affirm part of that with my whole heart: children are. They will surprise you and devastate you and inspire you a million times a day (they will also try to put a Lego in your ear, or call you boring and annoying, or puke on your shoulder). But so often they are remarkably resilient in the face of extraordinary challenges, whether upheaval or illness or injury, challenges that would crumple me immediately. They can draw pictures and sing songs and love, still, and hope.

The second clause there, the “usually turns out well” is another story. Many survive, with various scars, and others die. All of these children deserve so much better.

I don’t understand what possesses anyone to break someone else’s bones, let alone allegedly a nurse in the care of vulnerable infants. I would love to live in a world where that could never happen. But since, brutally, unfortunately, it does, it’s worth understanding a bit more about these injuries and trying to recognize them. Remember to be suspicious of a kid who doesn’t cruise with bruises; the fracture without a plausible mechanism or a fracture in a child who isn’t walking yet; a baby with bruising on their ears (or their torso or neck). These patterns aren’t just statistics; they’re children like Javeon. They may be in your local library, sitting next to you on the bus, or at your neighbor’s house. Your attention might save their life.

This was hard to write, and probably to read. Thanks for hanging in there. If you have questions, or if you have found this helpful, or if you want to rail against these various systems for doing a crummy job, hit up the comments.

Not his real name.

Unfortunately intimate partner violence is another matter.

To see how few pediatricians there are in your state trained in this or any other subspecialty, click here. It would be fun if it wasn’t so depressing!

The care is not the same. I understand many lack access to pediatric hospitals, especially in rural communities and less populous areas. But if there’s a choice to be made, choose a pediatric hospital for your child.

References

Haney S, Scherl S, DiMeglio L, Perez-Rossello J, Servaes S, Merchant N; and the Council on Child Abuse and Neglect; Section on Orthopaedics; Section on Radiology; Section on Endocrinology; and the Society for Pediatric Radiology. Evaluating Young Children With Fractures for Child Abuse: Clinical Report. Pediatrics. 2025 Jan 21:e2024070074. doi: 10.1542/peds.2024-070074. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39832712.

Kellar K, Pandillapalli NR, Moreira AG. Calcium and Phosphorus: All You Need to Know but Were Afraid to Ask. Clin Perinatol. 2023 Sep;50(3):591-606. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2023.04.013. Epub 2023 Jun 1. PMID: 37536766.

Palusci VJ, Botash AS. Race and Bias in Child Maltreatment Diagnosis and Reporting. Pediatrics. 2021 Jul;148(1):e2020049625. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049625. Epub 2021 Jun 4. PMID: 34088760.

Tsai, Andy & Coats, Brittany & Kleinman, Paul. (2017). Biomechanics of the classic metaphyseal lesion: finite element analysis. Pediatric radiology. 47. 10.1007/s00247-017-3921-y.

Tiyyagura G, Leventhal JM, Auerbach M, Schaeffer P, Asnes AG. Improving the Care of Abused Children Presenting to Community Emergency Departments: The Evolving Landscape. Acad Pediatr. 2021 Mar;21(2):221-222. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.09.008. Epub 2020 Sep 19. PMID: 32961336.

Tiyyagura G, Asnes AG, Leventhal JM. Improving Child Abuse Recognition and Management: Moving Forward with Clinical Decision Support. J Pediatr. 2023 Jan;252:11-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.08.020. Epub 2022 Aug 17. PMID: 35987368.

Slingsby B, Bachim A, Leslie LK, Moffatt ME. Child Health Needs and the Child Abuse Pediatrics Workforce: 2020-2040. Pediatrics. 2024 Feb 1;153(Suppl 2):e2023063678F. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-063678F. PMID: 38300005.

Child Abuse and Neglect. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed 1/28/2025. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/child-abuse-and-neglect/?srsltid=AfmBOop0oCNcMWgb02jwpyNhTVNlpjWcke4_Ry6Cm9L_ex7fqMqsAIlS

Disclaimer: The content provided in Couch Nap is for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It does not establish a doctor-patient relationship. Always consult with your healthcare professional regarding any medical concerns or decisions. The views and opinions expressed here are our own and do not represent the positions, policies, or opinions of our employers or any affiliated organizations. While we strive for accuracy, the information presented here may not apply to your unique situation.